This article is an excerpt from Chapter 4 of Damages, by Lara Christine Johnson

For more information on this topic, check out the Damages book on BarBooks™. The print version of this book will be available later this year.

____________

- 4.3 PROOF OF PAIN AND SUFFERING AS AN ELEMENT OF NONECONOMIC DAMAGES

- 4.3-1 General Principles

To prove pain and suffering, the most significant general principle is that evidence must be presented showing that the plaintiff’s pain and suffering is causally related to the defendant’s conduct. See Crawford v. Seufert, 236 Or 369, 388 P2d 456 (1964). Sometimes that proof must be in the form of medical testimony; but sometimes the nature of the injury is such that laypersons or the jury can determine causation without the help of an expert.

In Ouma v. Skipton, 267 Or App 406, 341 P3d 124 (2014), the trial court struck the testimony of a chiropractor because he failed to testify that the injuries he treated were, to a reasonable degree of medical probability, caused by the collision. The trial court granted a motion for directed verdict on noneconomic damages on the ground that the plaintiff had failed to present sufficient evidence of causation. On appeal, the court noted that the record contained testimony by the plaintiff that he had fractured his tooth in the collision, evidence from which the jury could find causation without expert medical testimony. “Although we agree,” the court explained,

with the trial court’s conclusion that plaintiff necessarily would have to introduce expert medical testimony in order to establish causation with respect to the other injuries alleged in the complaint, we previously have held that defendant is not entitled to a directed verdict on an entire claim where there is sufficient evidence to permit a finding that the defendant’s conduct caused some part of the injuries alleged.

Ouma, 267 Or App at 409 (citing Wheeler v. LaViolette, 129 Or App 57, 61, 877 P2d 665 (1994)).

The severity of a plaintiff’s injuries will bear on the amount of proof required for noneconomic damages; “no severe physical injury can occur without involving mental distress.” Rostad v. Portland Ry., Light & Power Co., 101 Or 569, 582, 201 P 184 (1921); see also Smitson v. S. Pac. Co., 37 Or 74, 95, 60 P 907 (1900) (holding that damages for future pain and suffering of double amputee was not an erroneous jury instruction). Evidence of continued pain 18 months after an accident “establishes a probability that for sometime in the future plaintiff will suffer pain.” Odrlin v. Dugan, 137 Or 140, 142, 1 P2d 599 (1931); accord Nelson v. Tworoger, 256 Or 189, 192, 472 P2d 802 (1970).

If the plaintiff is seeking damages for permanent injuries, the existence of a scar two years after an accident is sufficient evidence of permanency. Kelley v. Light, 275 Or 241, 243, 550 P2d 427 (1976); Senkirik v. Royce, 192 Or 583, 593–94, 235 P2d 886 (1951).

- 4.3-2 Proof from Medical Practitioners

Although expert medical testimony may not be required to prove future pain and suffering, it is a common practice that can be effective. See Hecker v. Union Cab Co., 134 Or 385, 392, 293 P 726 (1930); Kelley v. Light, 275 Or 241, 550 P2d 427 (1976). As a matter of trial tactics, the plaintiff’s counsel will likely present medical testimony to explain the future course of the injury and how it will affect the plaintiff’s life.

* * * * *

- 4.3-3 Other Types of Proof

The plaintiff’s testimony about his or her own condition is always competent evidence on the issue of past and future pain and suffering. Skeeters v. Skeeters, 237 Or 204, 231, 389 P2d 313, reh’g den, 237 Or 242, 391 P2d 386 (1964) (plaintiff’s testimony held sufficient evidence of his paralysis to go to the jury on the question of whether such paralysis actually existed); Frangos v. Edmunds, 179 Or 577, 589, 173 P2d 596 (1946). Nonmedical witnesses may testify about the plaintiff’s declarations of present pain or suffering or about the witness’s own observation of the plaintiff’s behavior while in pain, such as limited activity. Frangos, 179 Or at 593 (testimony of plaintiff’s wife); Weygandt v. Bartle, 88 Or 310, 319, 171 P 587 (1918). In Fieux v. Cardiovascular & Thoracic Clinic, P.C., 159 Or App 637, 978 P2d 429, rev den, 329 Or 318 (1999), the court held that a patient was not required to present expert testimony on the issue of negligence or emotional distress when a surgeon allegedly left a clamp behind during open heart surgery, thus requiring another surgery. “[I]njured plaintiffs are entitled to claim damages for mental anguish, which plaintiffs may establish through their own or other lay testimony.” Fieux, 159 Or App at 641 (emphasis omitted).

In addition to testimony from the plaintiff and other lay witnesses, day-in-the-life videos may be helpful to communicate the effects of an injury on the plaintiff. See Arnold v. Burlington N. R. Co., 89 Or App 245, 248, 748 P2d 174, rev den, 305 Or 576 (1988) (over defendant’s objections, videotape admitted into evidence because it “communicated to the jury effectively, and perhaps better than words could do, what plaintiff’s life as a double amputee was like”).

* * * * *

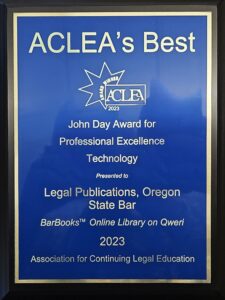

On June 8, 2022, the BarBooks™ online library relaunched on a new, more user-friendly platform called Qweri by Lexum, Inc. The relaunch was the culmination of several years of work by the Legal Publications Department.

On June 8, 2022, the BarBooks™ online library relaunched on a new, more user-friendly platform called Qweri by Lexum, Inc. The relaunch was the culmination of several years of work by the Legal Publications Department. The BarBooks™ online library is one of the highest rated member benefits that the Oregon State Bar offers to its membership. Members can also purchase subscriptions for their support staff.

The BarBooks™ online library is one of the highest rated member benefits that the Oregon State Bar offers to its membership. Members can also purchase subscriptions for their support staff.